Difference between revisions of "Basic electricity:1.2 Electric Charges"

(Created page with "== Neutral state of an atom == Elements are often identified by the number of electrons in orbit around the nucleus of the atoms making up the element and by the number of protons in the nucleus. A hydrogen atom, for example, has only one electron and one proton. An aluminum atom (illustrated) has 13 electrons and 13 protons. An atom with an equal number of electrons and protons is said to be electrically neutral. == Positive and negative charges == Electrons in the o...") |

|||

| (13 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

={{PAGENAME}}= | |||

== Concept of Charge == | |||

In all atoms, there exists a number of electrons that are loosely bound to its nucleus<ref>Basic Electrical Engineering, UA Bakshi, VU Bakshi, Technical Publications Pune</ref>. Such electrons are free to wander about, through the space under the influence of specific forces. Now when such electrons are removed from an atom it becomes positively charged. If excess electrons are added to the atom, it becomes negatively charged. | |||

== Unit of Charge == | |||

The charge on an electron is so small that it is not convenient to select it as the unit of charge<ref>Basic Electrical Engineering, VK Mehta and Rothi Mehta, S. Chand & Co. Ltd.</ref>. In practice, coulomb is used as the unit of charge i.e. SI unit of charge is coulomb abbreviated as C. One coulomb of charge is equal to the charge on 625 × 1016 electrons, i.e. | |||

:: <math>1 ~coulomb ~=~ Charge~ on~ 625 \times 10^{16} electrons</math> | |||

Thus when we say that a body has a positive charge of one coulomb (i.e. +1 C), it means that the body has a deficit of 625 × 1016 electrons from normal due share. The charge on one electron is given by ; | |||

:: <math>Charge~ on~ electron = -{1 \over {625 \times 10^{16}}} = {-1.6 \times 10^{-19}}~C</math> | |||

== Neutral state of an atom == | == Neutral state of an atom == | ||

[[File:Atom_Aluminum.jpg|center|Aluminum Atom|class=img-box]] | |||

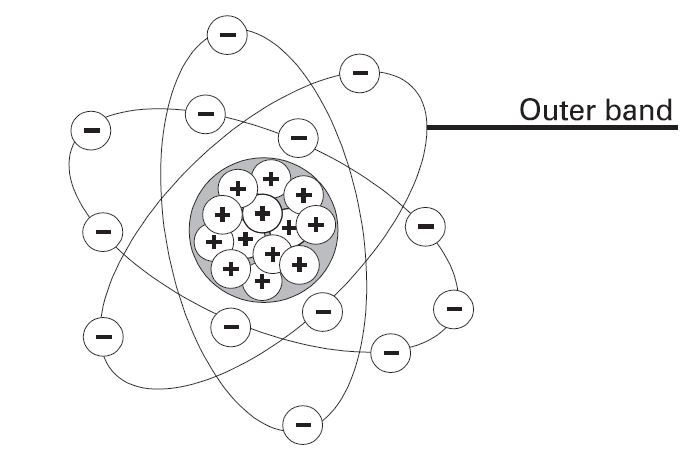

Elements are often identified by the number of electrons in orbit around the nucleus of the atoms making up the element and by the number of protons in the nucleus. A hydrogen atom, for example, has only one electron and one proton. An aluminum atom (illustrated) has 13 electrons and 13 protons. An atom with an equal number of electrons and protons is said to be electrically neutral. | Elements are often identified by the number of electrons in orbit around the nucleus of the atoms making up the element and by the number of protons in the nucleus. A hydrogen atom, for example, has only one electron and one proton. An aluminum atom (illustrated) has 13 electrons and 13 protons. An atom with an equal number of electrons and protons is said to be electrically neutral. | ||

== Positive and negative charges == | == Positive and negative charges == | ||

Electrons in the outer band of an atom are easily displaced by the application of some external force. Electrons | [[File:Charges.jpg|center|Charges|class=img-box]] | ||

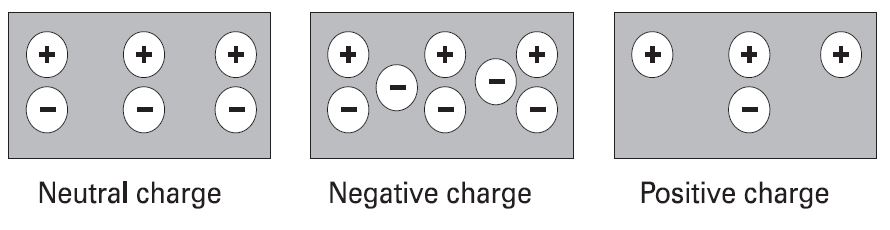

Electrons in the outer band of an atom are easily displaced by the application of some external force. Electrons that are forced out of their orbits can result in a lack of electrons where they leave and an excess of electrons where they come to rest. The lack of electrons is called a positive charge because there are more protons than electrons. The excess of electrons has a negative charge. A positive or negative charge is caused by an absence or excess of electrons. The number of protons remains constant. | |||

== Attraction and repulsion of electric charges == | == Attraction and repulsion of electric charges == | ||

[[File:Repulsion-attraction.jpg|center|Repulsion & Attraction|class=img-box]] | |||

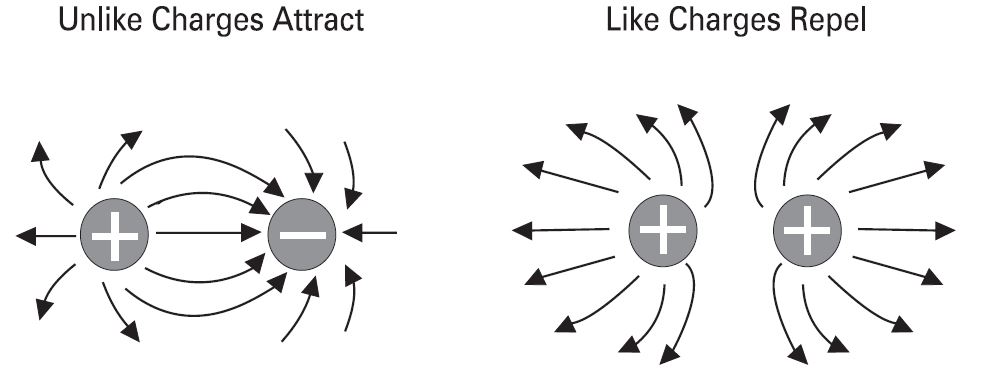

The old saying, "opposites attract" is true when dealing with electric charges. Charged bodies have an invisible electric field around them. When two like-charged bodies are brought together, their electric field will work to repel them. When two unlike-charged bodies are brought together, their electric field will work to attract them. The electric field around a charged body is represented by invisible lines of force. The invisible lines of force represent an invisible electrical field that causes attraction and repulsion. Lines of force are shown leaving a body with a positive charge and entering a body with a negative charge. | The old saying, "opposites attract" is true when dealing with electric charges. Charged bodies have an invisible electric field around them. When two like-charged bodies are brought together, their electric field will work to repel them. When two unlike-charged bodies are brought together, their electric field will work to attract them. The electric field around a charged body is represented by invisible lines of force. The invisible lines of force represent an invisible electrical field that causes attraction and repulsion. Lines of force are shown leaving a body with a positive charge and entering a body with a negative charge. | ||

== Coulomb's Law == | == Coulomb's Law == | ||

During the 18th century a French scientist, Charles A. Coulomb, studied fields of force that surround charged bodies. Coulomb discovered that charged bodies attract or repel each other with a force that is directly proportional to the product of the charges, and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them. Today we call this Coulomb's Law of Charges. Simply put, the force of attraction or repulsion depends on the strength of the charged bodies | During the 18th century a French scientist, [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles-Augustin_de_Coulomb Charles A. Coulomb], studied fields of force that surround charged bodies. Coulomb discovered that charged bodies attract or repel each other with a force that is directly proportional to the product of the charges, and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them. Today we call this Coulomb's Law of Charges. Simply put, the force of attraction or repulsion depends on the strength of the charged bodies and the distance between them. | ||

== Atomic Theory == | |||

The concept of charge is based on atomic theory <ref>Basic Electrical Engineering 4th Ed., C. L. Wadhwa, New Age International (P) Ltd., Publishers</ref>. An atom has positive charges (protons) in its nucleus and an equal number of electrons (negative charges) surround the nucleus making the atom neutral. Removal of an electron leaves the atom positively charged and the addition of an electron makes the atom negatively charged. The basic unit of charge is the charge on an electron. The mks unit of charge is the coulomb. An electron has a charge of 1.062 x l0<sup>-19</sup> C. | |||

When a charge is transferred from one point in the circuit to another point is constitutes what is known as electric current. An electric current is defined as the time rate of flow of charge through a certain section. Its unit is ampere. A current is said to be of one ampere when a charge of 1 coulomb flows through a section per second. | |||

Mathematically, | |||

:: <math>i = {d_q \over d_t} </math> | |||

If charge q is expressed in coulomb and time in second, 1 amp flow of current through a section is equivalent to approx. flow of 6.24 x 10<sup>18</sup> electrons per second through the section. Yet another method of defining electric current (1 amp) is as the constant electric current in two infinite parallel conductors separated from each other by 1 m, experience a force of 2 x 10<sup>-9</sup> N/m. | |||

==References== | |||

<references /> | |||

Latest revision as of 09:53, 3 January 2022

1.2 Electric Charges

Concept of Charge

In all atoms, there exists a number of electrons that are loosely bound to its nucleus[1]. Such electrons are free to wander about, through the space under the influence of specific forces. Now when such electrons are removed from an atom it becomes positively charged. If excess electrons are added to the atom, it becomes negatively charged.

Unit of Charge

The charge on an electron is so small that it is not convenient to select it as the unit of charge[2]. In practice, coulomb is used as the unit of charge i.e. SI unit of charge is coulomb abbreviated as C. One coulomb of charge is equal to the charge on 625 × 1016 electrons, i.e.

Thus when we say that a body has a positive charge of one coulomb (i.e. +1 C), it means that the body has a deficit of 625 × 1016 electrons from normal due share. The charge on one electron is given by ;

Neutral state of an atom

Elements are often identified by the number of electrons in orbit around the nucleus of the atoms making up the element and by the number of protons in the nucleus. A hydrogen atom, for example, has only one electron and one proton. An aluminum atom (illustrated) has 13 electrons and 13 protons. An atom with an equal number of electrons and protons is said to be electrically neutral.

Positive and negative charges

Electrons in the outer band of an atom are easily displaced by the application of some external force. Electrons that are forced out of their orbits can result in a lack of electrons where they leave and an excess of electrons where they come to rest. The lack of electrons is called a positive charge because there are more protons than electrons. The excess of electrons has a negative charge. A positive or negative charge is caused by an absence or excess of electrons. The number of protons remains constant.

Attraction and repulsion of electric charges

The old saying, "opposites attract" is true when dealing with electric charges. Charged bodies have an invisible electric field around them. When two like-charged bodies are brought together, their electric field will work to repel them. When two unlike-charged bodies are brought together, their electric field will work to attract them. The electric field around a charged body is represented by invisible lines of force. The invisible lines of force represent an invisible electrical field that causes attraction and repulsion. Lines of force are shown leaving a body with a positive charge and entering a body with a negative charge.

Coulomb's Law

During the 18th century a French scientist, Charles A. Coulomb, studied fields of force that surround charged bodies. Coulomb discovered that charged bodies attract or repel each other with a force that is directly proportional to the product of the charges, and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them. Today we call this Coulomb's Law of Charges. Simply put, the force of attraction or repulsion depends on the strength of the charged bodies and the distance between them.

Atomic Theory

The concept of charge is based on atomic theory [3]. An atom has positive charges (protons) in its nucleus and an equal number of electrons (negative charges) surround the nucleus making the atom neutral. Removal of an electron leaves the atom positively charged and the addition of an electron makes the atom negatively charged. The basic unit of charge is the charge on an electron. The mks unit of charge is the coulomb. An electron has a charge of 1.062 x l0-19 C.

When a charge is transferred from one point in the circuit to another point is constitutes what is known as electric current. An electric current is defined as the time rate of flow of charge through a certain section. Its unit is ampere. A current is said to be of one ampere when a charge of 1 coulomb flows through a section per second.

Mathematically,

If charge q is expressed in coulomb and time in second, 1 amp flow of current through a section is equivalent to approx. flow of 6.24 x 1018 electrons per second through the section. Yet another method of defining electric current (1 amp) is as the constant electric current in two infinite parallel conductors separated from each other by 1 m, experience a force of 2 x 10-9 N/m.